This month’s reading group (which will take place March 13, 6:30 pm to 8 pm at And Then Books, Rossville) pulls back from the global perspective we took in January and February and begins a focus on North America—future installments will narrow our focus down to our specific region and bring our attention forward in time. This month’s set of readings—taken from three books and one book chapter—take us across the entire continent, looking at the ways in which Native peoples before initial European contact interacted with the land and were in turn shaped by it. I chose these readings—Nature and History in the Potomac Country: from Hunter-Gatherers to the Age of Jefferson; Feeding Cahokia: Early Agriculture in the North American Heartland; "Hohokam Impacts on Sonoran Desert Environment"; and Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California's Natural Resources—because they give us insights into a broad range of Native lifeways and interactions with the wider environment. If there is one single take-away from this set of readings that I’d hope readers come away with, it is the sheer diversity of those lifeways and interactions, such that we cannot speak of some unified “Native American way of life” for the entire continent, to put it mildly. The environmental history of the Native peoples of California stands in quite sharp contrast to that of the Hohokam and other peoples of the desert Southwest—a contrast that raises the question of conscious choice on the part of Native peoples, something we’ll tackle during our discussion.

I’ll go over each reading briefly below—these are excerpts so some context is helpful to understand them better—but first I’d like to point out what I at least see as things that all, or pretty much all, Native peoples had in common in North America prior to European contact in terms of their relationship to the landscape and to other living things (notice I am avoiding for the moment the term “agriculture”). One of the big ones, though it is easy to forget, is that north of Mexico there were no domesticated animals aside from dogs; in Mexico and points south there were a few more domesticates (most of which were really semi-domesticated) to be sure but not that many more (for more on Maya agriculture pre-conquest, see this deep-dive I wrote a little while back). Vitally, whereas the Eurasian Neolithic transition to agriculture went hand in hand with the domestication of sheep, goats, cattle, and others, no American Native peoples had access to the “Neolithic kit.” This meant that manuring fields with domesticate herds was simply not a possibility. It also meant that the zoonotic diseases to which Afro-Eurasian peoples have been exposed for the last several thousand years had no footprint whatsoever in the Americas, a major factor in the demographic collapse of early modernity once those diseases were introduced.

I do not think this basic divergence can be over-stressed: without domesticated meat reserves on the hoof, wild animal populations remained vital, indeed indispensable to even the most agriculturally committed peoples of the Americas. Hunting and fishing would remain a core part of all Native peoples’ subsistence, which meant that wild lands held commonly by families, clans, polities, and so forth would also remain vital. And without concentrated manure supplied by domesticated animals agriculturalists had to find other options for dealing with decreased soil fertility over time due to farming. As such we can see many shared strategies across the Americas—but somewhat surprisingly perhaps we also see some very intensive, very long-lived in one place agricultural systems emerge, as in the case of the Hohokam. On the other end of the spectrum, some Native peoples never became agriculturalists at all, while many—the majority arguably, certainly in North America—continued to draw upon wild plants and trees for a considerable amount of subsistence. If for most Afro-Eurasians the Neolithic “agricultural revolution” represented, ultimately, an inevitable path with no going back, this was much less true in the Americas. But how different peoples over the last ten thousand years or so situated themselves in respect to their wider environment has otherwise varied a great deal on this continent, as I hope these readings will reveal.

Nature and History in the Potomac Country: from Hunter-Gatherers to the Age of Jefferson: Our first selection is set in the vicinity of what would become the capitol city of the young United States, the neighborhood of the Potomac River and the Chesapeake Bay. This is the land upon which my own ancestors first set foot on, and mattock and hoe into, the soil of this continent, starting in the later half of the seventeenth century, and I have myself spent nearly a decade living there. The chapters that I have excerpted here cover the emergence of agriculture among the Native peoples of the Potomac and neighboring areas, making an argument for how the environments of the Potomac region shaped the responses and configurations of these peoples (and, if you read the entire book, the Europeans and Africans who would begin settling and seizing the landscape in earnest from the mid-seventeenth century forward). As you read these chapters, along with the specific details of land, ecology, and cultures, note how all of these interact and which seem—in this author’s telling at least, feel free to disagree!—to have primary agency in the unfolding of history.

Feeding Cahokia: Early Agriculture in the North American Heartland: This is, as far as I know, the best exploration of how agriculture developed in our part of the world, and challenges some long-standing ideas, particularly about the inevitability of maize-centered agriculture. While this is not a self-conscious work of environmental history, I think it fits into our framework pretty well—agriculture always involves interacting with (to put it mildly!) the environment, and as you will see in these chapters that was especially true for pre-maize growers in the South and Midwest. Pay attention to the spectrum of choices and interventions that ancient inhabitants of the South and Midwest made in relation to wild, cultivated, and semi-cultivated plants. As is true in Tending the Wild, Native peoples intervened for their own purposes in many ways, not just those we would identify as “agriculture,” but also in ways we might describe as “management,” things like controlled burns and directed plantings in otherwise “wild” spaces. Also crucially the chapters I’ve selected give you a good sense of the gradual and non-inevitable process of plant cultivation over thousands of years in the Eastern Woodlands: while we do eventually reach the fascinating (and now largely lost or obscured) suite of cultivated grains that preceded maize, there was no sudden jump into full-time farming. The polyculture that would support Eastern Woodlands peoples was the result of many years of many different people interacting with plants and environments; and while we will not read about in these selections, these now obscure plants would long hold their own in the presence of maize.

"Hohokam Impacts on Sonoran Desert Environment": This article (book chapter in fact but de facto a stand-alone article) is pretty self-explanatory and detailed, even if you’ve never heard of the Hohokam. What stands out about their mode of agriculture is its intensity and its long-livedness. That said, assuming you read these selections in order, you will see some similar practices operating at the edges (literally!) of Hohokam agriculture. Pay attention as well to what the political and social structures were like in order to sustain long-lived intensive agriculture, agriculture that needed not just nutritional replenishment but also sophisticated (both technically and socially) irrigation techniques.

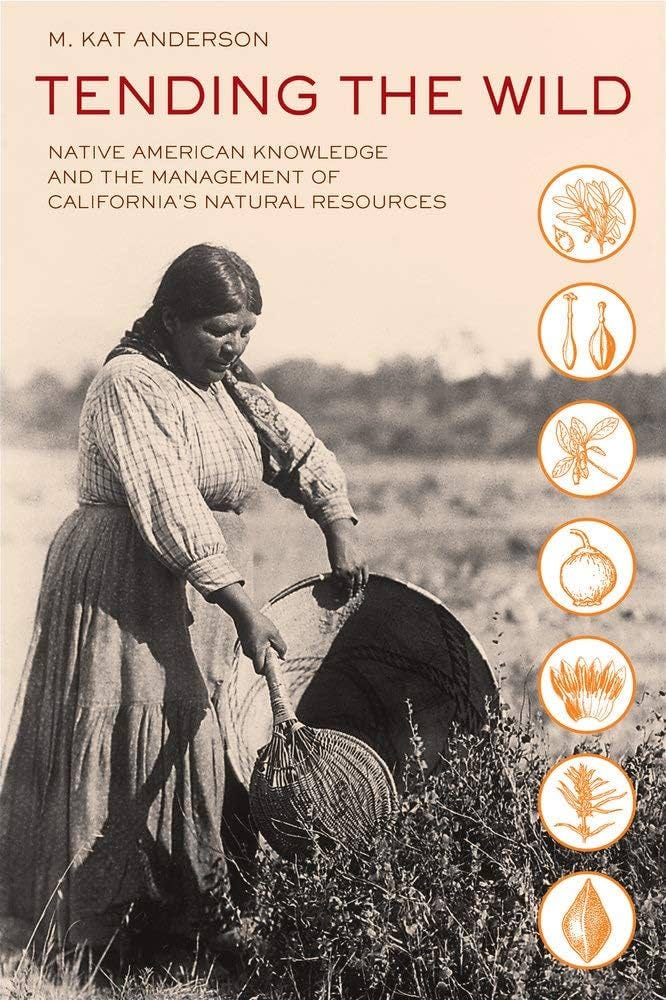

Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California's Natural Resources: We conclude on the other side of the continent with a selection from the definitive work on the environmental and resource use history of Native peoples of what would become the state of California. By now—assuming you make it this far in the readings!—there will be some familiar themes but also some sharp disjunctures. Unlike the other peoples discussed above, full scale agriculture was never embraced by the diverse people groups of California. Certainly the option was available—the Hohokam were not that far away geographically, and certainly maize agriculture had a much longer path to take in the east of the continent than the west. So then as you read it is worth asking why these various peoples committed themselves to “horticulture” and “management of the wild.” This selection is also a good opportunity to reflect on how culture shaped interactions with the environment, and vice versa—if we had the time we would go into cultural attitudes towards nature, the wild, agriculture, and so forth, across various Native peoples, attitudes which unsurprisingly varied a great deal, from seeing the wild as threatening and in need of submission to rather more harmonious perspectives. Finally, we can reflect on what the take-aways might be for us today—are there lessons for agriculture, social systems, and so forth, among California Native peoples and all the others that we have surveyed?