The Lost Canebrakes of the American South

Further Explorations in the History and Recovery of Native Agroecosystems

It is almost a truism of natural history, yet we still tend to forget it: the natural landscapes that we see and experience on a day-to-day basis are not permanent nor immovable, the species assemblies we come to know in a given place have their own history, have changed in the past and will change again in the future. Further, the ecosystems that we see in a given moment might reflect very poorly or not all what would have been present in the same location a century ago, to say nothing of before European colonization.

I do not think I myself really grasped this reality until, a couple of decades ago now, the effects of the hemlock woolly adelgid had begun to spread into the Southern Appalachians in force. I have watched in my lifetime—I’ll be forty later this year, so we are not talking about an especially long length of time—one of my most beloved species of tree largely disappear from the Southern Appalachians east of the Plateau, with the remaining groves at the western edge of the range imperiled but still subsisting, for now at least. I was intellectually aware of the loss, which took place long before my birth, of the great American chestnut, and have known since childhood how to spot its lingering ghostly presence—slowly decaying hulks on the forest floor, sprouts from roots, doomed to die before bearing nuts. But what a forest dominated by American chestnuts actually looked like, I had, and have, no real idea, no solid reference point, no tactile memory. I remember what the Southern Appalachians were like before the mass loss of the hemlocks, and can see the transformation that has occurred in my own lifetime.

There are many other examples of historical transformations—losses, gains, changes—whose traces are still there on the landscape, but which can be easily overlooked, invisible without the right reference points, and past the point of living human memory retaining any trace of them. Things like land clearance, agriculture, mining, development, and so forth are all pretty obvious (though, ironically, their traces often fade faster than some of the less obvious human-caused transformations such as invasive introductions). The most dramatic recent (in geological time that is) period of ecosystem transformation came in the transition from the late Pleistocene to the early Holocene: here on the southern fringe of the Appalachians jack pine forests gave way to the ancestors of today’s extremely diverse deciduous tree dominated forest types, for instance, at least speaking generally. The evidence we have—cores from the ancient sagponds on Pigeon Mountain, for instance—let us paint in broad strokes, no doubt missing many ecological niches that may have persisted through the last Ice Age into the present warm period.

We can speak much more confidently of the changes in the last few hundred years, transformations that began with the slow but steady introduction of Old World agricultural methods and attendant species, starting with Hernando de Soto’s entrada, as native peoples adopted and adapted Eurasian species into their agricultural practices. This stream of change became a river as Euro-American settlers, often with enslaved African-Americans in tow, seized and settled more and more of the American South over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; with the advent of full industrialization the river became a flood. Every ecosystem in the South has been changed by this long historical process, a process whose agents of change range from livestock to steel plows to chattel slavery to introduced pathogens, all part of an increasingly globalized world of material and biological exchange and displacement.

One of the most momentous changes is one that probably no one alive today can fully tangibly appreciate, putting it in league with the better known near-extinction of the American chestnut, though its effects were more geographically widespread. I am referring, as you might have guessed based on this essay’s title, of the collapse of the American rivercane (Arundinaria gigantea). I say collapse because, unlike the chestnut, our native canes are still very much present, and indeed relatively common. But much like the lingering presence of the chestnut the rivercane of today is but a ghost of what it once was. To say that rivercane was once a major species of the Southern landscape is an understatement. Canebrakes—stretches of land, often riverine, completely dominated by rivercane, to the exclusion of trees in many cases—once covered thousands of continuous acres, providing habitat for animals great and small, including some restricted to rivercane habitats, including some insects for whom rivercane is an indespensable part of their life cycle (and hence an indication of the great antiquity of this plant and its ecosystem).

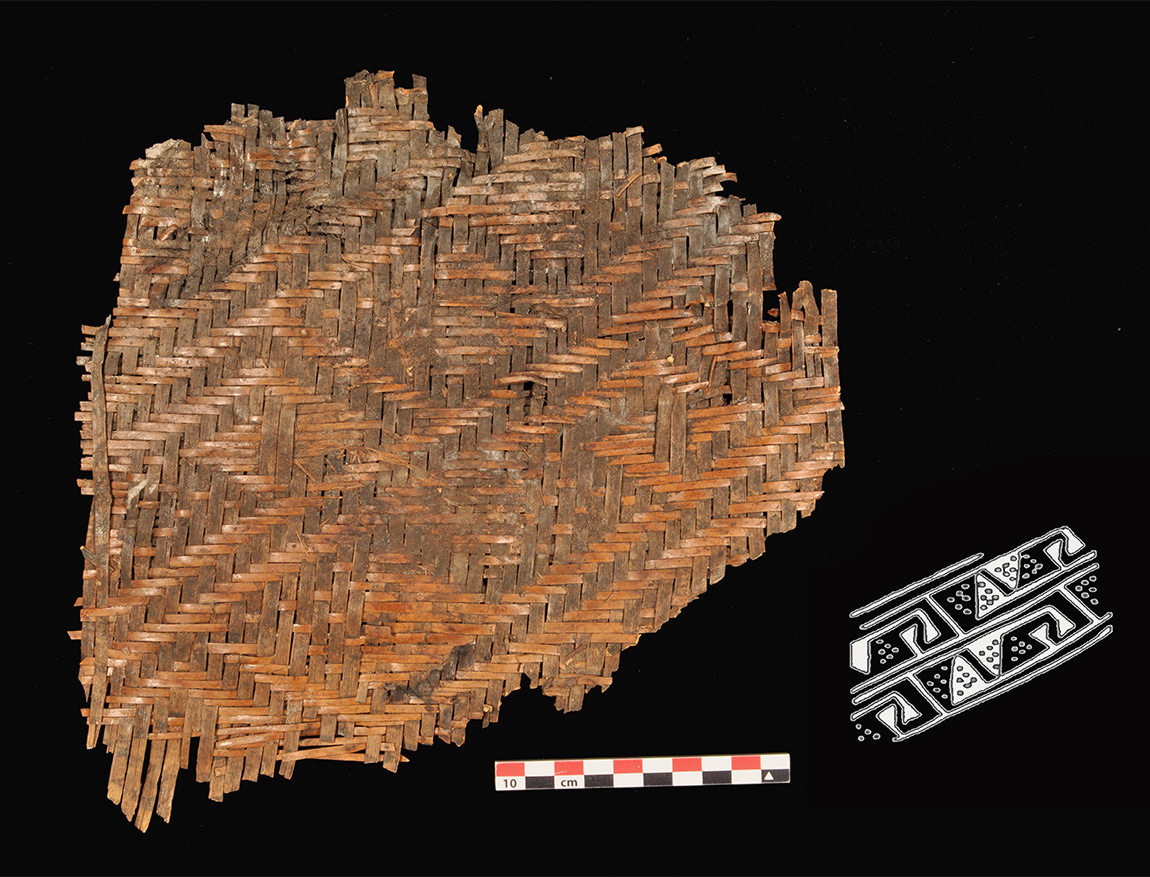

These great canebrakes were, at least in part, anthropogenic “agroecosystems” it seems, often maintained by periodic deliberate burning carried out by native peoples of the South. They maintained these ecosystems for the very good reason that rivercane was a crucial part of everyday life in the greater South: it served as a food source, as fuel, as building material, and as material for baskets, mats, and other objects. Archeological evidence indicates such uses dating well back into the Archaic, perhaps even before. And while our climate is usually not very good for the long-term preservation of organic remains like rivercane, a handful of dry rockhouses have given up remnants of ancient basketwork made from rivercane, such as these two examples from an Arkansas site, their iconography typical of the wider Mississippian cultural complex:

Canebrakes were not just repositories of things useful directly to humans: they were important game reserves, sometimes set apart specifically for that purpose, as canebrakes provided food for wild animals and protective habitat. Humans—especially the Muscogean peoples whose historical territory lies at the epicenter of rivercane’s natural distribution—also found rivercane useful for protection, with thick canebrakes sometimes replacing wooden stockades as defensive measures. Other canebrakes probably persisted with minimal human intervention, especially those that had reached truly prodigious sizes.

Despite their size, ubiquity, and usefuleness, the great canebrakes of the South are no more, or at least virtually no more (there are a few scattered instances of recent planting and nurture, though I have never seen one myself). What happened? Georgann Eubanks describes succintly in her book Saving the Wild South:

The sweet flavor and nourishing properties of young shoots of river cane would ultimately lead to the species’ near demise. As Bartram noted, young cane served as ready feed for wild game and for horses and cattle, an asset recognized by the Indigenous peoples, who took care not to overgraze it. European settlers soon learned the benefits of cane to nourish their farm animals. Cattle who ate emerging cane gained weight and produced better butter and milk.

The presence of wild-growing cane usually indicated a high water table and good soil. In its early stages of growth, the nutritional value of the plant is at its peak. Settlers sought the rich bottomlands where cane grew, letting their animals graze the land before grubbing out the roots to till the soil for crops. The historian Mart Stewart says the loss of river cane is an under-appreciated and key component of “the long tale of extraction and decline—of the eighteenth and nineteenth century South.”

And so, coupled with the loss of renewing fire, the canebrake was eaten into oblivion, plowed up, ignored, and in the end, lost.

Canebrakes lasted, as far as I can tell, into some point in the early twentieth century, though I could not tell you when the last significant canebrake finally disappeared. Efforts to revive them have occurred, but sporadically; more common are stretchs of rivercane dominated understory alongside streams, though even those are threatened by vigorous invasive species like privet. Culturally, while sporadically still in use, imported, invasive east Asian bamboos have tended to replace some of the uses of rivercane (fishing poles, for instance). On the whole, this really is a lost ecosystem, an entire major aspect of the Southern landscape that is now almost unimaginable, not even surviving in some remote pocket akin to old growth forests.

The historical canebrake falls into a category of ecosystem for which we do not really have good terminology: it was (as we’ve seen, the past tense is most appropriate today) wild in the sense that no one engaged in regular management, beyond, perhaps, periodic deliberate burnings, coupled with communal governance, ensuring that species within the canebrake were not hunted too heavily, perhaps also ensuring that certain areas of canebrake were not converted to agriculture. At the same time, unlike most nature preserves today—for which the above would be quite intuitive approaches—the canebrake was a cultivated space in the sense that it was used, fairly intensively at times, for human needs, as a repository of raw materials, as a source for hunted game, and at times as a means of defense. For it to ever truly recover there would probably need to be reconstituted need for it as a plant, and an understanding of commonly held agroecosystems as places of both natural refuge and human benefit.

We have started to make some limited use of American rivercane at a couple of affiliate locations in our community agriculture network: the site with the greatest potential is no doubt the Chattanooga Valley community garden and food forest, which lies on the floodplain of Chattanooga Creek, and was almost certainly a canebrake at some point in the past. I have been unable to find any historical documentation, but the existing floristic profile of the creek’s valley south of Chattanooga strongly suggests a mixture of wet grassland and canebrake. American rivercane grows as a robust understory component along the creek, and might well be the closest thing to a historical canebrake in our immediate vicinity. In places just east of Flintstone the rivercane is quite dense, but I have been unable to locate any spots where it is the dominant plant to the exclusion of trees. It occurs sporadically along other streams in our area, though I do not know of any stands so dense as those along Chattanooga Creek (if you know of other locations in or near Chattanooga, let us know in the comments!). What it might look like to incorporate into a community food forest is not yet totally clear to me: as a fast growing and easily spreading plant, it will require ample space and some kind of containment measures, akin to other vigorous spreaders like mints. We will also need to find ways to utilize it—all of the same sorts of things one would do with bamboo can be done with rivercane, but perhaps we can revive some of the other cultural practices that made use of this plant. Who knows—in a few years maybe we’ll be carrying fruits and vegetables in baskets woven from our rivercane! If that happens, expect to read about it in this space.